Last September 2024, at the United Nations Summit of the Future, world leaders adopted a landmark agreement: the Pact of the Future, to tackle the most pressing global challenges, accelerate sustainable development and financing for development.

With August being the month to commemorate International Youth Day, I reflect on the long list of international agreements that formally recognise the need to embed and strengthen meaningful youth participation at national and international levels (The Pact of the Future formally does it in articles 36 and 37, respectively). While “meaningful youth participation” has long been the mantra of youth-focused global development initiatives, it no longer reflects the urgency of today’s political realities. The concept implies inclusion without agency, inviting young people to the table but rarely letting them shape the menu.

Young people are not just beneficiaries of future policies, but active agents of change who should be involved in shaping the future they will inherit. This includes ensuring that youth have the means and resources to be heard, and that their perspectives and vision are considered in all relevant decision-making processes. That goes beyond participation and must be something more aligned to institutionalised power-sharing. It demands a structural and cultural transformation in how institutions perceive and engage with young people.

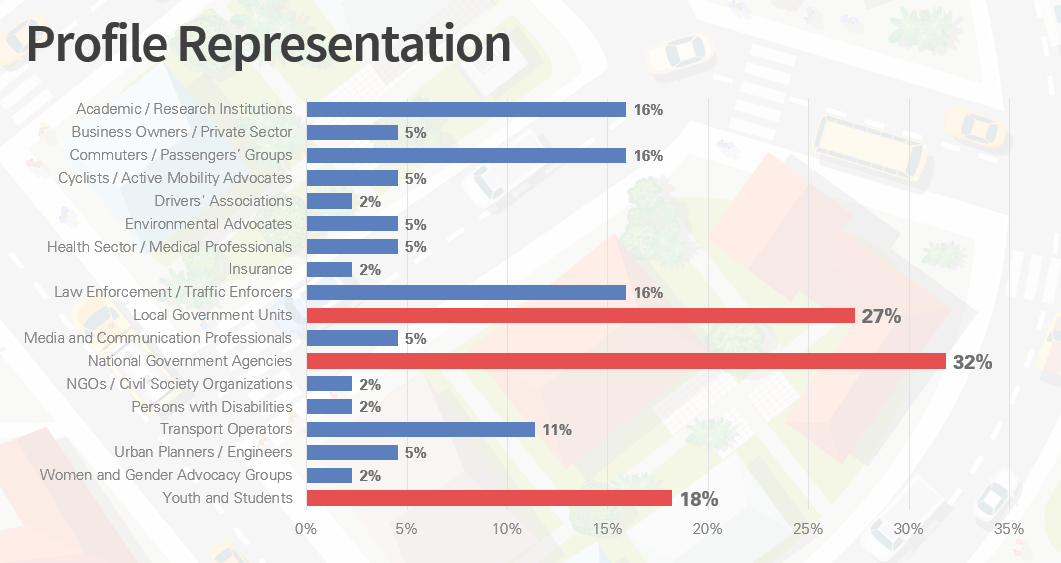

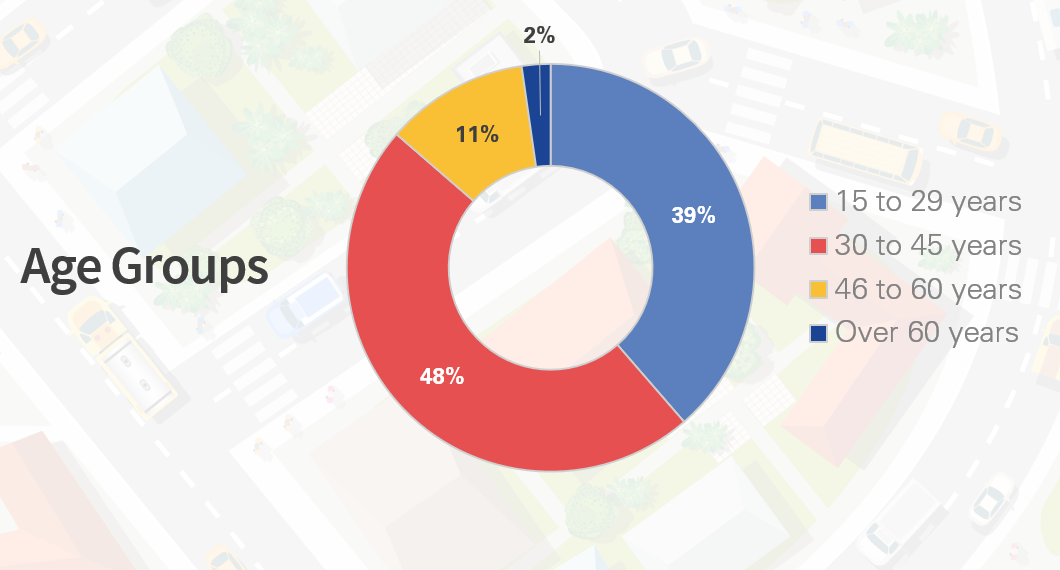

When it comes to road safety and sustainable mobility, there must be a foundational change in how young people are included and perceived, as mostly, they seem to be playing the “beneficiary role”. Young people, as one of the most affected populations of unsafe transport systems and mobility inequities, have to play a more active role in designing and implementing solutions that reflect their lived realities. What they need, how they interact with the system, how they behave, what they share with their peers, what challenges and inequalities they faced, are just a few of the multiple questions they could help answer with real representation and power-sharing.

Without power-sharing, road safety and sustainable mobility remain a technocratic exercise; with it, they become a democratic mandate. When communities, especially youth and marginalised groups, are co-authors in mobility planning, streets move from being engineered abstractions and become expressions of collectiveness, shaped by lived realities and local priorities.

Power-sharing with youth in road safety and sustainable mobility could bring multiple benefits to increase the efficiency and effectiveness of policies. When real, youth can use their creativity, fresh perspectives and innovative mindsets to influence inclusive and equitable street design and actionable norms. The fact that they have exercised agency since the beginning could foster co-ownership, accountability, transparency, and higher chances of compliance, while policies could also remain flexible and responsive to changing needs.

In the road safety and sustainable transportation field and any other field, youth need political design, not performative spaces. The rhetoric of youth inclusion has too often translated into forums, panels, and consultations that prioritise visibility over agency. What young people require is political design: intentional, institutional mechanisms that embed their influence into the machinery of governance. Youth engagement doesn’t mean much without mechanisms for co-authorship of policy, oversight of implementation, and accountability within power structures. Designing youth roles politically means rethinking democracy, not as a stage for speaking up, but as a way to distribute authority, power and responsibility. That requires re-shaping political, economic, and social frameworks to be flexible, responsive, and co-created with young people at the table.

YOURS – Youth for Road Safety was honoured to be part of this launch, invited by FIA Foundation, a long-standing partner whose collaboration continues to strengthen global efforts for youth-centred and sustainable mobility. Representing YOURS at the event, Sana’a Khasawneh, Senior Advocacy and Public Affairs Manager, joined global experts and policymakers to discuss how child-centred design can contribute to safer and more inclusive cities. Participating in initiatives like this reinforces our shared mission: creating environments where young people can move freely, safely, and confidently in cities that truly work for everyone.

YOURS – Youth for Road Safety was honoured to be part of this launch, invited by FIA Foundation, a long-standing partner whose collaboration continues to strengthen global efforts for youth-centred and sustainable mobility. Representing YOURS at the event, Sana’a Khasawneh, Senior Advocacy and Public Affairs Manager, joined global experts and policymakers to discuss how child-centred design can contribute to safer and more inclusive cities. Participating in initiatives like this reinforces our shared mission: creating environments where young people can move freely, safely, and confidently in cities that truly work for everyone.